I was invited to teach at the Translational Research Program (TRP) at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine in the Fall of 2019. This is a Master’s Degree program for individuals interested in designing innovative solutions in the healthcare space. The cohort in the class of 33 consisted of one-third physicians, one-third other healthcare professionals including nurses, midwives, and medical administrators, and one-third technical specialists including designers, and engineers.

The Course

The course I co-taught was “Projects in Translational Research” where students pair up with medical stakeholders to design interventions using Design Thinking methods. The class was divided into six groups, each tackled a different problem. One of these groups chose to explore the challenges of adopting virtual care among Canadian medical professionals. The group was made up of three medical doctors, all working full time in academic institutions in various specialties, one medical researcher and one technologist. All of the group members were female and one was expecting a baby before the end of the course.

I have been teaching Design Thinking or User-Centered Design for almost 20 years in industry, at various schools, and in different faculties. This was my first time teaching in the medical space. Although I have done some consulting projects in the medical space, and have medical professionals in my immediate family. The first pronounced difference I noticed during this course was the determination with which some of the groups approached their projects.

User Needs Analysis

This virtual care (VC) group capably executed all course deliverables, conducting primary research among their extensive medical networks, and delivering deep insights into their chosen problem space. In conducting their background research and User Needs Analysis the team discovered three primary issues:

- Workflow disruptions: Physicians did not want the introduction of virtual care into their practice to disrupt to their daily workflows in their already busy schedules.

- Payment uncertainty: In Canada, provincial governments fund all medical services and have control over which services are funded. Virtual care at the time was largely not a funded service for many physicians.

- Physicians were interested in VC: Physicians in Canada were interested in changing their current practices to support patients’ requests for virtual care. At the time, however, virtual care appointments were only supported through the proprietary, usability challenged process via Ontario Telehealth Network (OTN).

The team’s research also identified the following barriers of VC adoption by physicians: system barriers, lack of administrative infrastructure, lack of (?) convenience, educational needs, and concerns for patient privacy.

Design Process

The team developed personas, scenarios, and storyboards for how to persuade and educate hesitant physicians to adopt VC into their practice. They then developed low-fidelity prototypes of potential interventions to overcome the identified barriers. Low-fidelity prototyping is a valuable tool used in early design work to embody an early solution idea and communicate it to the target audience. For example, low-fidelity prototypes of digital systems can be drawn on paper, and low-fi service ideas can be acted out – a process also called body storming. The team’s low-fidelity prototypes intentionally diverged in focus to span the VC problem space and included: Flyer for VC Education Rounds, Website for VC Support, VC Referral Form, VC Metrics Dashboard, and Clinical Guidelines for VC.

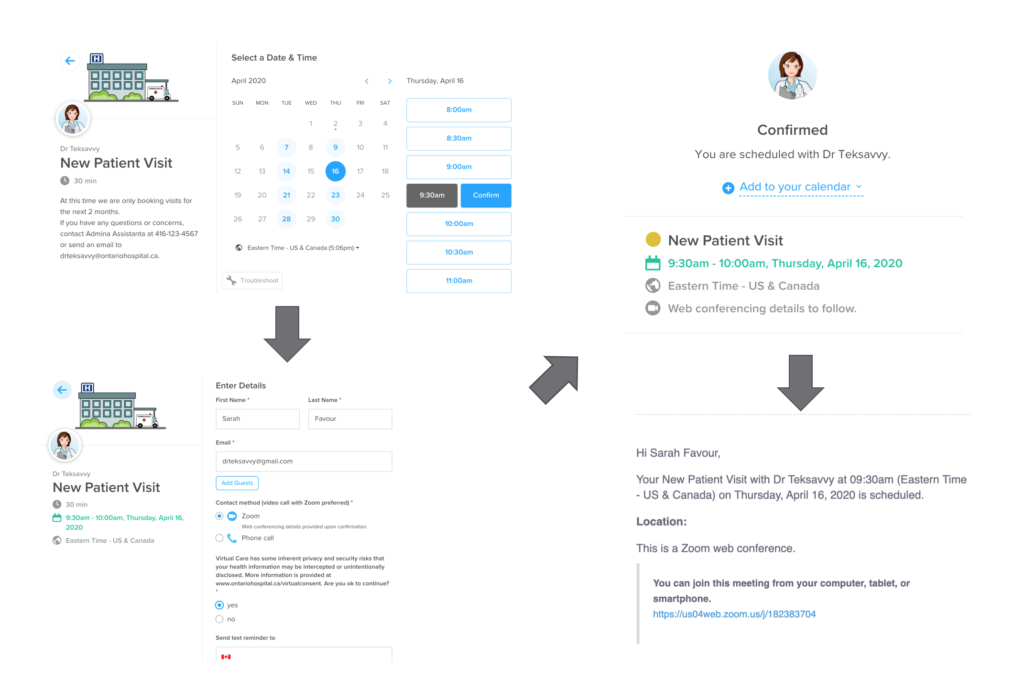

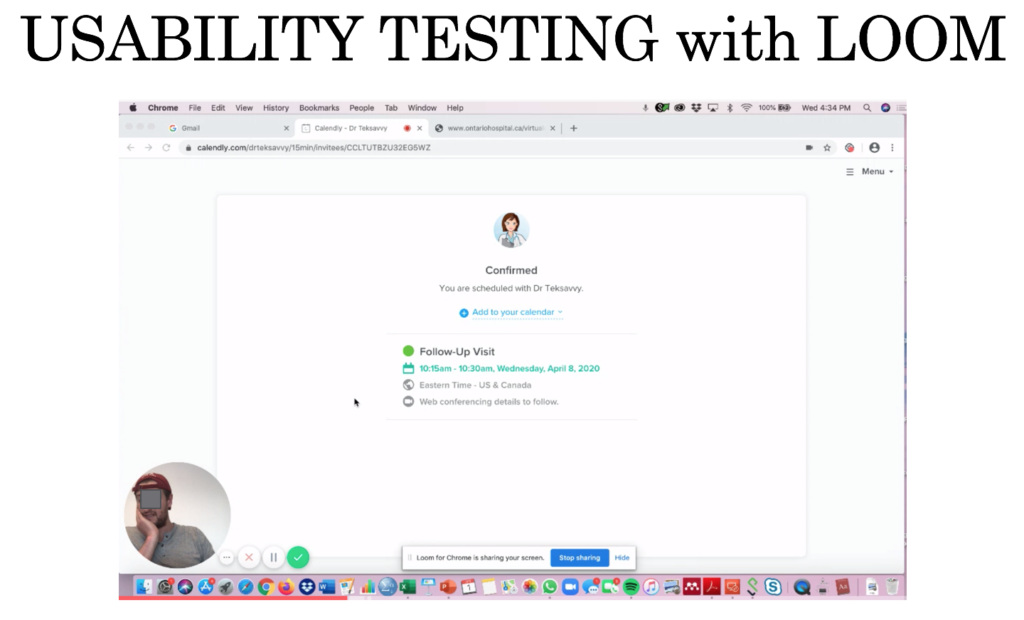

After testing their individual low-fidelity prototypes in class, the team combined insights to produce a higher-fidelity prototype. They iterated their prototype design while honing their newly acquired skills in the User Experience Research Methods of Cognitive Walkthroughs (designers explore their solution by enacting hypothetical users in realistic scenarios of use), Heuristic Evaluations (designers assess their solution following a specific set of predefined best practice guidelines), and Usability Testing (observing real people, ideally drawn from the target audience, interacting with the design to identify challenges and obstacles in task performance). They learned the value of Qualitative User Experience Research (less concerned with large sample sizes and statistically significant results and more with observed obstacles during real usage), which differs significantly from the traditional medical research practices they were familiar with.

COVID-19 Lockdown

As the class was approaching the final weeks, COVID-19 forced classes to be moved to an online format. Our first remote class was on March 12, and by March 16, all University of Toronto classes were being held online. Healthcare providers in the class were now facing significantly increased stressors in their daily work. Many were required to pull out of other commitments including TRP classes, to focus on their professional commitments.

As COVID-19 limited patient visits to hospitals, patient appointments were moved to a virtual format. To allow this to happen, the OHIP March 13 bulletin removed the “Payment uncertainty” barrier identified by the team’s primary research.

In support of the government’s efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 in Ontario, the Minister of Health has made an Order under the authority of subsection 45(2.1) of the Health Insurance Act to temporarily list as insured services the provision of assessments of or counseling to insured persons by telephone or video, or advice and information to patient representatives by telephone or video, as well as a temporary sessional fee code.

The previously mentioned OTN system was up until that point the only way to conduct virtual appointments and be remunerated for them. This system had a reputation among physicians as being overly bureaucratic and under-resourced, with a high user learning curve, requiring additional billing paperwork, and prone to dropped video calls. The March 13th OHIP announcement provided Ministry funding for telephone and video visits over any format. What had previously been one of the main barriers to rolling out virtual care across physician practices, vanished almost overnight.

Predicted Intervention

Almost prophetically, the VC team’s high-fidelity prototype had proposed an educational session on March 20th delivered by Dr. Ilana Halperin to discuss the implementation of Virtual Care. On March 20th, OntarioMD hosted an actual webinar to help physicians incorporate virtual care into their practice. Topics that were addressed included discussion of new billing codes, workflow integration, technology choice, and patient selection, similar to the learning objectives the VC group had proposed. And Dr. Ilana Halperin happened to be one of the speakers! This online session was attended by 300 Ontario physicians. The group’s visionary prototype design had been implemented independently of their input! They could have wrapped their project right then; victorious!

The Pivot

However, physician training instills the instinct and drive to problem solve and help in emergency situations. COVID-19 was an emergency. Doctor’s offices and clinics had shut down. Ontario, along with the rest of the world, came to a standstill as shelter-in-place edicts were announced by governments worldwide. The physicians’ day jobs kept them on the frontline dealing with the pandemic in hospital emergency departments and inpatient settings. The new challenges ignited innovative opportunities to problem solve and help.

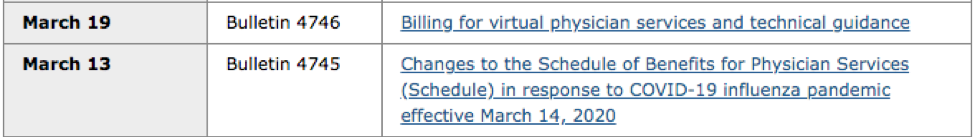

The VC team took their newly acquired Design Thinking and User Experience Research skills to the COVID-19 front lines. Identifying needs for novel interventions and workflows, the group applied their foundational research insights, updated their Experience Maps, and pivoted their design.

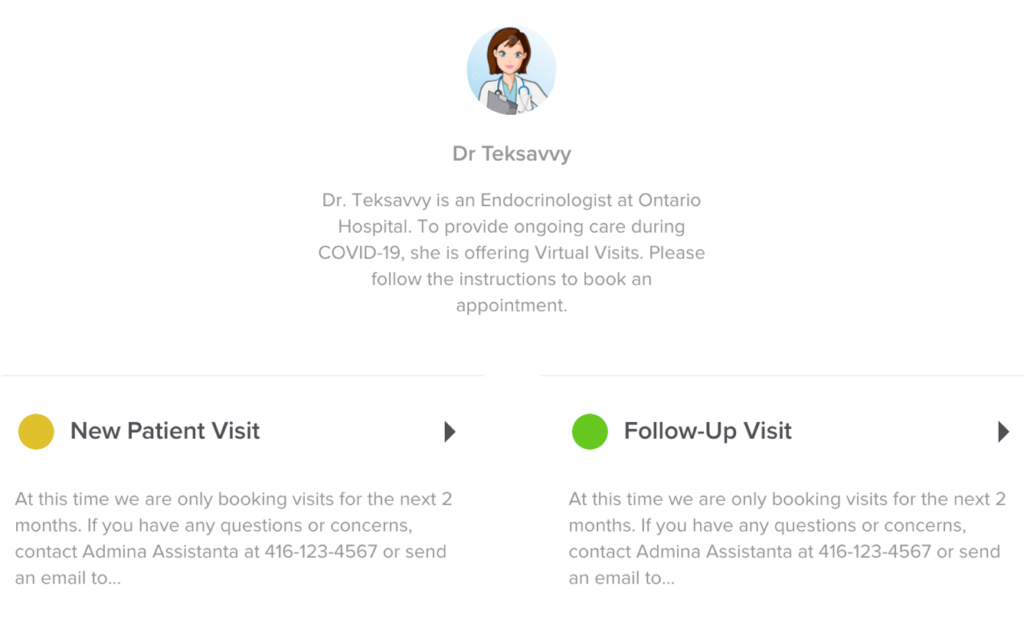

Much to the surprise to their instructors, at the final project presentation the team presented a fully functional design that allowed patients to self-book virtual appointments, which automatically scheduled video or phone visits, and sent out reminders. They had piloted this design in record time following the course methodology and had begun to implement this into their medical practice.

Reflections

The group reflected on their takeaways from the “Projects in Translation Research” course:

I really believe that this course challenged me to think outside of the box and apply new concepts to real-world problems in healthcare.

The major take-away point from this course for me is the need for and importance of usability testing in general. In health care, this is often a neglected tool, and interventions are implemented without any iteration. This is perhaps why hospitals are stuck with archaic electronic patient records that are extremely difficult to navigate. These system inefficiencies can definitely be improved through prototyping, usability testing, and the various design tools we learned through this course.

Each group member was invested in the problem. Had we not spent the number of hours doing primary and secondary research, it would have been difficult to pivot. Each of my group members brought complementary strengths that we built on. … I will use the skills I have learned from this course, usability testing with a low-fi prototype, heuristics, and cognitive walkthrough for design to future prototypes. Working in a group with non-clinician members was very beneficial to understand aspects that I previously would not have asked related to IT, industry, and administration. In the future, I will seek out non-clinician perspectives. I have gained a greater appreciation for the value and the groundwork needed to design a prototype, whether it is a flyer, an application, or a service.

I previously assumed as an academic physician my work time would be divided between clinical responsibilities, teaching responsibilities, and research. However, this course has shown me that I want ‘design work’ to be a part of what I do. I found it challenging but also incredibly stimulating and rewarding. I love to solve problems; I love creating; I love finding tangible solutions. To do this in healthcare to address the real problems is the dream.

Conclusions

As a User Experience consultant with 30 years of experience, I have been fortunate to have worked on many interesting projects in diverse industries. My favorite part has always been demonstrating the value of different points of view in any particular problem space, and how this diversity of views leads to more robust and innovative solutions. As an educator, my passion is to open the eyes of my students to our own limited perspectives, our keyholes. This project demonstrated the power, generalizability, and value of User Experience, User-Centered Design, and User Experience Research methods. It contributed to innovative solutions that addressed real-world problems in real-time. This confirms my heart-felt belief in the impact of scaling our reach by sharing our knowledge and experience with receptive audiences who want to make a difference and will not hesitate to use all their knowledge, effort, and power to make a better world.

About Us

ILONA POSNER is a User Experience Consultant and Educator based in Toronto, Canada. She enjoys bridging different worlds: industry and academia. An avid traveler, she can’t wait to resume travels, in the post-pandemic world. www.ilonaposner.com

I want to thank the VC project team for their hard work and dedication to their project despite the challenges of COVID-19 and childbirth! This project was conducted by the team of Dr. Jana Dengler MD, MASc, Michelle Jennett, HBA, MSc., Dr. So Youn Rachel Kim, MD, FRCSC, Tobi Lam, MSc., Dr. Yasbanoo Moayedi, MD.

This project was part of the Translational Research Program https://trp.utoronto.ca/

I want to thank Joseph Ferenbok, Ph.D., the Director of TRP program who gave me the opportunity to teach this course. Dr. Payal Agarwal MD my co-instructor in this course and Fahimeh Rajabiyazdi my invaluable teaching assistant in this and several other courses.